Anti-personalization: The best ad for one, is the best ad for all

Samuel Brealey and Michael Taylor Source: WARC Exclusive, June 2022. Reposted with permission.

Why it matters

The tools we use mean absolutely nothing if we don’t understand the market itself or how people buy and react to things – often in ways that seem totally irrational. The temptation in the last ten years has been to see advertising and marketing as a feat of engineering, due to the explosion of new technology and to outsize its importance in the marketing toolset.

Takeaways

Marketers’ enthusiasm for personalisation at scale may be needlessly adding complexity while reducing effectiveness because of a lack of attention to marketing fundamentals.

In general, the best ad for one audience is the best ad for all audiences.

Segmentation is based on the idea that you should break up your total market into groups to better tailor your ads to what each group wants. However, it is only useful if there are noticeable and distinct differences within a market that can be capitalised on.

The further you segment, the smaller the total market gets – inevitably reducing the potential value of the market, in terms of both its cash value and the total quantity of customers.

If a business has to rely on deals and promos rather than memory and positive associations then it is not a strong brand, as there is no preference beyond price.

‘Always on’ advertising to the total market is beneficial to all of those who can afford to do so, using advertising that is consistent, creative and memorable.

Over the last ten years, marketers and advertisers have become obsessed with the idea that more data is better; that never-ending complexity and one-to-one communication is the future, negating not only history itself but also the evidence which is piled high against the idea of ideas such as ‘personalisation at scale’.

Part of the issue lies in a lack of fundamentals; you don’t know what you don’t know. No marketer wants to be the first one to hold up their hands and say, “we don’t need more data, let’s get back to basics”. Focusing on fundamentals is what actually works, but the latest shiny thing is what’s perceived to work by the wider business, and it takes discipline to stay the course.

Marketers who have not taken the time to learn beyond the industry press or their immediate peers are marketers who get swept up in the lofty promises of suppliers. We live in an age dominated by technological progress, so it’s understandable that fear of missing out is a huge driver of behaviour.

But that’s all it is, and we need to recognise this. This is neither cynical nor dismissive; it’s the practical and honest reality of marketing.

Segmentation: A greater slice of the pie, is just that

Segmentation is a simple term that most people understand. The issue lies in how it’s used, as with most things in marketing. This simple concept is based on the idea that you should break up your total market into groups, to better tailor your ads to what each group wants. But the problem lies with the assumed implication that you have to break it up. That isn’t always the case.

Segmentation is only useful if there are noticeable and distinct differences within a market that can be capitalised on.

Slicing and dicing it up for the sake of it leads to superficial differences being stated as important when they are not. And the smaller the segment, the less statistical significance it has.

A good example of segmentation is one that focuses on dividing a market based on its commercial appeal. This could be a segmentation that is as simple as ‘Small businesses struggling with financial admin that outsource their accounting within a 25-mile radius of our office’.

This segmentation states the potential customer, the issues their business is facing and the constraints in which the marketer must plan based on internal resources, in this case determined by geography.

This is a far cry from the common examples of differentiation and personas, where markets are subdivided into countless smaller groups with hyper-specific criteria around the individual traits of people. Generally loaded with information but little about the financial value or quantity, just vague ideas of who the customer is.

This information is neither useful, nor practical because the resources required to meet the exact criteria cannot realistically scale with a growing business.

That’s one nail in the head for personas and micro-targeting.

The second nail is the mathematical reality of over-segmentation. Here is an example:

1,000,000 customers make up the total market.

500,000 are female.

150,000 have blonde hair.

60,000 of these blonde-haired women have children.

40,000 of these blonde-haired women that have children work full time.

7,000 of them are classed as ‘passionate’ about homeware.

The further you segment, the smaller the total market gets, inevitably reducing the potential value of the market, in terms of both its cash value and the total quantity of customers.

A good example of how this should look is:

1,000,000 customers make up the total market.

400,000 are women within 20 miles of stores (70% of sales are in-store, 30% online).

250,000 have an income level within the range of our typical customers.

This is a far simpler segmentation that gives a far greater market to address. With this information you can then perform further work to understand the media they use as well as research into category entry points to understand their behaviour. This example does not seek to superficially group people based on character traits which have absolutely no influence on purchase behaviour.

The basics of segmentation in the classical sense are often all that are needed to define the parameters in advertising and media choices, rather than an over-reliance on behavioural signals from platforms such as Facebook. A simple example would be a small B2B business that segments its customers by industry and proximity, as it deems them to be most likely to purchase due to existing familiarity and a historical appeal to a more localised part of the market. The ‘personalisation’ in this context is aimed at communicating a message and offer that works for that particular segment, a segment that is ‘bottom of funnel’.

If that small business is also targeting another industry in a new location, with little awareness then the messaging will be different. But this begs the question, is that even classed as personalisation? In our opinion, we would argue that it isn’t, based on the accepted view of personalisation as something that intends to be as granular and ‘one-to-one’ as possible.

It’s quite ironic that digital marketing gurus often advocate micro-targeting, when those who dig deeper into Facebook’s educational material will find that they suggest at least 100,000 and preferably one million people in terms of audience size. The resources are there for those who know what they’re looking for.

Just because you won poker three times while wearing your red shoes doesn’t mean that the red shoes are an influential variable on that outcome. And the same applies to segmentation, a variable isn’t necessarily an influence.

The final point is data itself, the assumption that all data is good data. Those who understand data will be familiar with the idea of ‘cleaning’ data. And there is very little evidence that behavioural data captured by platforms is a predictor of purchase intent. Not to drag them into it again, but Facebook produced a study that showed no positive correlation between click through rates, clicks and engagement generally with the likelihood of purchase.

Evidently, one cannot reasonably argue that those who click more should be further segmented, as there is little value to doing so. It’s exactly the same as the red shoes and joker story – it’s a correlated variable, but it has no causal impact. So, default to broader segmentation and avoid the temptation to slice the cake into

ever smaller pieces based on ‘dirty’ data sending false signals.

Case study: The real-world evidence is plain to see, to those who look

As is often the case, the first client was also the most instructive, which is what Michael found during his time at Ladder. Each of the 200+ clients that followed, as Ladder grew into a 50-person growth marketing agency, saw success with the same playbook established with the client, Money Dashboard. They came to Ladder drowning in data. In fact, if you added up the conversions claimed by Facebook and Google Ads, affiliates, email, word of mouth and the blog, it added up to 150% of their actual app installs on any given day. They were double counting.

Ladder started on Facebook ads, where a consultant was using ‘proprietary software’ to personalise creative for 100s of micro-targeted audiences based on interwoven combinations of demographics, interests and behavioural segments. Ladder sliced the Gordian knot and did away with all but the top 10 audiences. Within a week performance was up 20%, but more importantly it became more stable and predictable in the coming weeks. It turns out many of those micro-audiences overlapped, and thus were cannibalising each other’s impressions, leading to random spikes and dips.

With that win under the belt, other pieces of the pie were taken one by one, consolidating multiple marketing tactics into one cohesive approach. Standardised tracking was the largest hurdle but, once completed, Ladder saw something interesting – conversions attributed to affiliates, email, word of mouth and even Google got their first touch from Facebook.

The blog was mostly read by existing users on the email list.

Word of mouth was strongly correlated with how much was spent on ads.

Most of Google turned out to be coming from the brand term.

It was the equivalent of a restaurant owner giving full credit for every new customer to the sign outside their door. Everyone who comes into the restaurant passes by that sign, so whatever drove them to come out to eat in the first place is being undervalued. Within a couple of months Ladder had cut investment in most of these channels, and used the budget saved to double down on what was truly driving incremental new users: Facebook ads.

As the optimizations and renewed focus proved successful, the team would update their marketing mix model to see what was driving incremental performance, independent of what Facebook and Google were telling them. This led them to plot out the diminishing returns curve and see where the channel would get saturated, so they could adjust spend upwards to hit their aggressive growth targets.

At the time there was concern of ‘putting all our eggs in one basket’, but the data was clear and there were limited resources. Any use of time that wasn’t optimising campaigns or testing new creative was a distraction.

As you can see from the case study above, it worked. With renewed focus they tested 100s of new creatives across 10 audiences. Multiple combinations of different concepts, formats, memes, taglines, images. Only about 30% of tests would succeed, and there were competitions internally about what creatives would win, which Michael frequently lost.

The ultimate performer was “Be good with money” which almost wasn’t used, because the team thought it was too ‘vague’. It drove 109x more installs at a 65% lower cost per install than would’ve been achieved with the best performing ad on the account when it was taken over.

Over these six months of aggressive testing, Ladder noticed something curious: the best-performing ad in one of the audiences, say targeting ‘students’, would also outperform other options when rolled out to different unrelated audiences like ‘frequent travellers’ or ‘working professionals’.

They were split tested multiple times because it flew in the face of all the ‘best practices’ that come out of the blogs of self-professed Facebook ‘gurus’.

There was no escaping it: the results were replicated enough times on Money Dashboard and also every other client Ladder worked with, in every industry. From other FinTech clients like Monzo Bank to enterprise scale B2B travel with Booking.com and smaller early stage startups like NextUp Comedy.

The overwhelming reality was and is that the best ad for one audience is the best ad for all audiences.

Personalisation realities: The unbalanced scales of ‘personalisation’

An unhealthy obsession with personalization stems from a misunderstanding of the economics of how modern auction-driven digital advertising platforms like Facebook work.

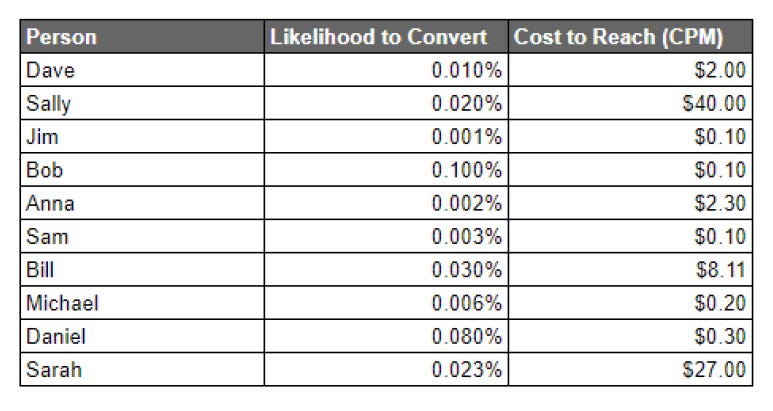

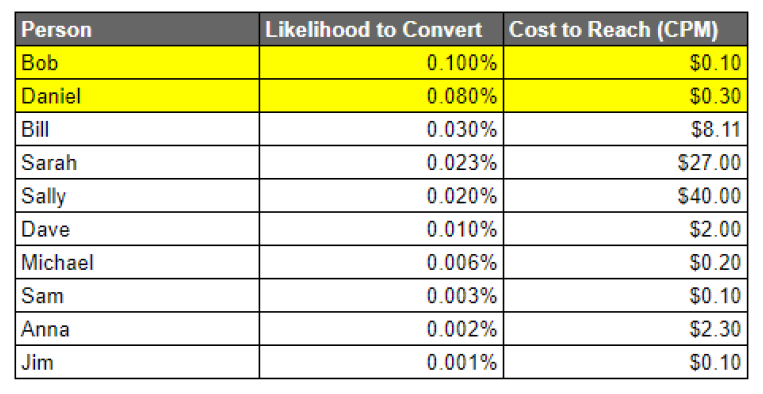

When you target an audience on Facebook it uses machine learning to estimate how likely each person in that audience is to convert, as well as how much it’ll cost to reach that person. CEOs with high disposable income or stay at home parents who manage household finances have more competition for their eyeballs than the average person, so it makes sense they’d cost more to reach. A simplified version might look like this:

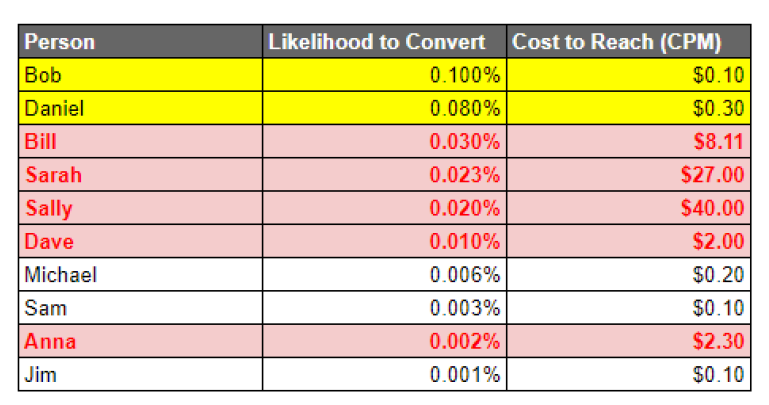

Facebook is incentivised to show adverts to the people who will engage with it most – or at least be least annoyed by it – so it targets people at the end of the buying cycle, who are in the market for your product. This often means people who have already been on your website and are likely to buy even without seeing an ad; one of the many attribution issues plaguing digital marketing. Additionally, you’ve set up budget constraints within the platform, so Facebook will want to find the cheapest people to reach within those who are highly likely to buy.

So far, so good. The ability to do this at scale is what makes Facebook a multibillion-dollar company. It’s also approximately how all modern ad platforms work; they all copied Google’s wildly successful auction model. The genius of that model, and the inherent difficulty that faces advertisers, is that to scale your ad budget you need to outbid the other advertisers in the auction. Unlike traditional advertising where if you buy more you can cut a deal, in modern auction-based ad platforms you face diminishing marginal returns where it costs more per thousand impressions (CPM) the more you need to spend.

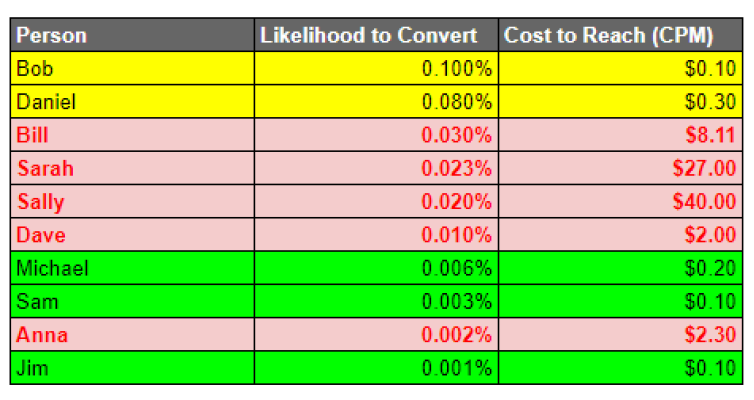

So, where do we go from here? You were turning a profit on the top 20% of customers that were both cheap to reach and highly likely to buy, but the next 40% of the audience are 10–100x more expensive.

There are cheaper people to target, but they’re far from making a purchase. We’re getting at the fundamental reason why performance marketing aka direct response – targeting that top 20% – is so effective using digital media. That is where its strength lies, predominantly. But it’s not the only way to use it, digital can be used for ‘top of funnel’ as well.

Those cheap and ‘out of market’ people might not be ready to buy right now, but if you advertise to them anyway and build the right memory structures and associations in their brains, they’ll think of you next time they purchase. The power of brand advertising if you get it right, is that you can influence the probability of purchase.

Brand is a big word. It means lots of things to lots of people but it’s often best to define it as securing future cashflows – it’s a longer-term endeavour that should be measured based on improving brand health metrics. That is, are you remembered when a buyer enters the category? Because it is often that on-the-spot thinking that leads to a purchase. And if a business has to rely on deals and promos rather than memory and positive associations then it is not a strong brand, as there is no preference beyond price.

Using advertising that is consistent, creative and memorable is how you do it. There is naturally going to be some overlap, but the point is that ‘always on’ advertising to the total market is beneficial to all of those who can afford to do so.

If the goal of brand advertising is to increase the likelihood of purchase through ‘cultural imprinting’, as described by Kevin Simler in “Ads don’t work that way”, then ‘personalised’ targeting is the exact opposite of what you should be doing.

The mechanism only works if the ad is highly conspicuous – you have to believe that everyone else saw it too – for buying the product to be a meaningful communicator of status or preferences. This type of advertising is costly precisely because it needs to be to be believable. The peacock grows illustrious feathers to show that it’s a healthy mate, while an unhealthy peacock can’t afford to waste the energy. The primary thing a Superbowl ad tells you about a company is that they’re doing well enough to afford a Superbowl ad, and buying their product is probably a safe bet.

Humans are weird, we don’t make sense, so it is counter to our nature to believe that humans are ‘rational optimisers’ who only purchase things based on price. There are many more levers that marketers must pull, and direct response isn’t the only one – and nor should it be.

An example of marketing frameworks

Marketers and advertisers often dig themselves into holes debating the exactness of models or frameworks. As the saying goes: all models are wrong, some are useful. The above examples illustrate the point that neither are completely correct, but if one only uses the left hand side, they start to believe there is a line in the sand that divides the two.

Many comments have been made on the work of Les Binet and Peter Field’s “The Long and Short of it” by people who didn’t care to read it properly. The binary split was not to be taken literally; it is about principles applied, not rules followed.

Marketers and advertisers would be wise to rid themselves of the pernicious myths that “brand advertising doesn’t need to perform”, or that “hyper-personalization using data is the only way to drive performance”. In truth it’s not ‘brand vs performance’, it’s ‘long term vs short term’ and ‘small scale vs large scale’. If you’re a small startup with less than 1% of your market, capture as much cheap existing demand as possible – in the long term you might be dead otherwise.

Hence the importance of marketing basics, like segmentation – you build an understanding of the market and go after those easy wins first.

As you grow and saturate the in-market audience and those easy-to-access segments, you’ll need to expand to ‘delayed response’ channels or ‘mid-funnel’ activity. For example, moving some budget from Google Ads where someone is searching for your product, to Facebook ads where they’re the right person but haven’t started looking yet.

Then, eventually, when all of the low hanging fruit is eaten, it’s time for large scale ‘brand’ advertising. Once immediate cash flow is secured, then longer-term budget investment should follow. That’s when marketers and advertisers can have a complete funnel where media is allocated to each stage, and each segment has the right approach, whether it’s lower-funnel activity for the active, in-market segments, or consistent and long-term advertising that’s focused on the larger market that isn’t quite ready to buy just yet.

Loyalty doesn’t build brands: What’s more ‘loyal’ than addiction?

There is no stronger argument for the case of loyalty than those that are physiologically addictive, and no stronger example than cigarettes. Nicotine is a drug that hooks people for decades, killing millions who just can’t drop the habit.

The first point is the purchase pattern of those who buy cigarettes, the most addictive legal substance on the market, as demonstrated using the example below on Twitter by Brandon Shockley of 160 over 90.

The evidence is staring us right in the face. If an addictive legal drug that kills millions a year doesn’t have repeat purchase as its main driver then nothing else will. And there is no spin or single data outlier than can be used to counter this. Because the NBD-Dirichlet is a scientific model, because it’s replicated across categories. Whether it’s Harley Davidson, LEGO or in this case cigarettes.

There are many discussions about how loyalty can be improved, most of which are on the side of explosive loyalty growth. These are pipedreams built on dodgy maths and mythical thinking.

Myths are part of the problem. The oft quoted “If you increase your loyalty by just 5% then you will double profits” is not quite what it seems. The example quoted used a loyalty percentage rate that went from 5% to 10%.

A 5% to 10% increase is a doubling of existing retention rates, it is not a 5% increase. There are no businesses that are able to double their retention rates, and those that might be incredible rare outliers are often companies that had serious issues with product or distribution, not with advertising, which is often where the discussion is.

The lesson here is that no matter what you do, the majority of your buyers will be occasional. They will not be buying frequently, and therefore it is important to ensure that you are advertising and marketing not just to the easy wins but that you expand the pool of possible customers as broadly as you can afford to.

Businesses must start small, vacuuming up those easy wins with good segmentation that finds them, using advertising and all the other tools at a marketer’s disposal, from pricing to distribution.

As a business grows and expands, then it has no choice but to expand its targeting to the broader market. And those businesses that are big must continue to do the same, in the knowledge that most of their customers are light buyers and no amount of clever consultancy bingo is going to change those outcomes.

Demand: The marketplace is loud, you have to shout

In conclusion, marketers and advertisers must recognise the importance of what we’ve always known. We must remember that no matter how promising or perfect something sounds it is healthy to be sceptical and approach things with caution. Time and time again the proponents of rapid change have neglected to remember that humans themselves do not change very quickly. We are much the same as we were 10,000 years ago.

In 1923 Claude Hopkins wrote Scientific Advertising, much of which holds true today, and next year the book will be 100 years old. Hopkins wasn’t some futurist predictor; he was just a man with experience in his business and knew how people worked. He understood what worked because he knew how the market worked. The tools we use mean absolutely nothing if we don’t understand the market itself or how people buy and react to things – often in ways that seem totally irrational and non-sensical.

The temptation of the last ten years has been to see advertising and marketing as a feat of engineering, due to the explosion of new technology and to outsize its importance in the marketing toolset. Advertising is not persuasive, yet it’s a myth that holds. Advertising is a weak force, but it’s a universal cost of doing business – it’s a tax you have to pay to grow.

But there is a right way and a wrong way, and if you focus too much on the individual you are forgetting the market itself. The age of ‘personalisation’ was just another brief hump in the road as everyone got a bit carried away. It found itself a place in the marketing toolkit, but it was not the replacement it was deemed to be – like all things in marketing, everything new just adds to the toolbox. And like all tools, it’s only as useful as the tradesman using it.

You can make your job easier and apply the basic principles of what we all need to know and combine it with the best of the tactical. If you understand your market, and you know what tools to use and how to communicate with them, then you can’t go far wrong from there.

This is fire. Well done.